A warning: If the thought of tens of millions of tiny spiders spinning a web 24 hectares – 60 acres – in size and crawling all over it scares the wits out of you, you might want to tread carefully over the following. Because that’s exactly what happened last month on a farmer’s field near McBride, about 220 kilometres east of Prince George. For reasons that area scientists don’t really understand, millions and millions of tiny black spiders called Halorates ksenius – they have no common name – became trapped in Russell Jervis’ clover field and started spinning webs.

Halorates ksenius is not a big spider. “One could fit comfortably on a Smartie with plenty of room to spare,” says Brian Thair, a cell biologist at the College of New Caledonia in Prince George. (Or to put it another way, it’s about as big as a capital “O” printed on this page.) A typical barbwire fence on wood posts surrounded the field about six kilometres east of McBride in the Robson Valley. Thair said it looked like the whole area was covered with an opaque, white plastic grocery store bag. The thin, elastic coasting was not soft and fluffy like webs built by individual spiders. There were about two spiders per square centimetre laying the silk, which first appeared in early October. Thair said the web showed great tensile strength – enough to put a handful of coins on it without them falling through. There were “in the order of tens of millions of spiders running frantically back and forth,” but they weren’t interacting with each other. It’s just because so many of them were in the field that the web grew and grew until at its largest, 60 acres, it was as big as the triangle-shaped field it covered. Thair had never seen anything like it before. “It was astounding to see,” he said. “I couldn’t believe my eyes. From two kilometres away it looked like a sheet of wet aluminium. It was the size of several city blocks. I have never in my 30 years as a biologist seen anything like this, in terms of quantity of spiders and quantity of web. Nothing even remotely approaching this.”

Most of the web is gone now. Storms have ripped it apart. But during October and into early November, Thair says, it was home to possibly hundreds of millions of tiny black spiders that just kept spinning and reproducing. That caused the web to grow so large depends on whom you ask.

Thair speculates that perhaps because of some unusual weather conditions in late summer and early fall, the spiders were unable to disperse. Normally, when young spiders reach reproductive age, they spin a thread of web – a silk parachute – which is then caught by a breeze and lifts them into the air. It’s called “ballooning.” The wind carries the thread, with the spider attached to it, for some distance before dropping it. Where the spider lands is where it makes its home. But Thair guesses that because of too much rain or an absence of wind, the spiders in Jervis’ field were unable to balloon, so they stayed where they were. Then they laid eggs, which turned into more spiders, which laid eggs and became yet more spiders. Added to that was the fact that for some reason – again Thair doesn’t know what it was – the adult spiders failed to die, so they kept on reproducing too. And on and on it went.

Since the spiders didn’t seem to care if an occasional insect stumbled into their construction, Thair doesn’t think it was built for trapping purposes. He suggests the spiders encountered an enormous quantity of high quality, nutritious prey to be able to accomplish this feat. But he’s also heard other suggestions. “Some people have said, ‘oh yes, well it’s a trampoline for aliens,’” Thair joked. “Or maybe it was an effort collectively by these spiders to try and catch a sheep.”

Robb Bennett, an entomologist with the BC Ministry of Forests disagrees. He says the “sheet of gossamer” was likely millions and millions of drag lines the spiders produced prior to dispersing. Drag lines, he says, are anchors that spiders produce routinely to keep them connected with the ground. Bennett says these spiders – what he calls “LBJs for Little Brown Jobs” – and others very like them, live commonly in the north and probably emerged from the ground looking for the highest points in the field from which to disperse.

However, because no one who saw the web saw any spiders dispersing, he can’t say for sure that a dispersal took place. Nor has Bennett ever heard of so many spiders behaving this way so far north. He’s never seen the phenomenon himself, but does have a photo of a similar event in the 1990s in Louisiana. Consequently, he speculates that it may have something to do with warm temperatures. Whatever the cause, Bennett agrees with Thair that it was extraordinary. Jervis, who has owned the land for 60 years, has never seen anything like it on his farm. “The first people who saw it [in early October] thought it was frost,” he said. “Then they realised it couldn’t be frost because there wasn’t frost anywhere else. It just kept growing and growing. Like everybody else, I’d never seen anything like it before.” Jervis plowed the field early this year, which meant that in addition to the stubble a few young plants were starting to sprout. They were covered in thick cobwebs.

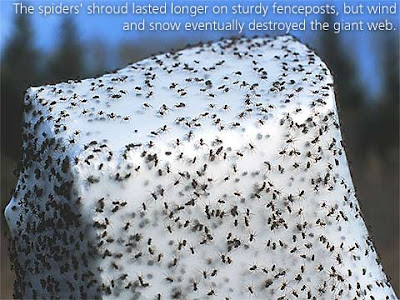

So were the fenceposts surrounding the field. So thick, says Thair, that he had to use a hunting knife to cut pieces of it away. (Comparatively, a spider’s web is stronger than steel.) The field itself was translucent, covered with just a thin layer of web that broke if you walked on it. But on the fenceposts, where it was thickest, it was like sheets of grocery store plastic, says Thair. “You know how when you stretch a piece of plastic tight over a bowl, your fingers bounce off it? That’s

what it felt like.”

Matthew Wheeler, a freelance photographer who lives in McBride, spent 5 hours one day taking pictures of the web and the spiders scurrying all over it. “The top of every plant and willow bush and fencepost was completely capped with this white sheet,” he says. “And the whole field was undulating in a delicate way in the breeze.” But if that sounds vaguely beautiful, there was a point when Wheeler said it was anything but. “There were spiders crawling all over my trousers and jacket, and they had started to spin webs over my camera bag. So I started to think about all the poison represented by all those millions and millions of spiders out there, and I started to wonder if I was being really stupid standing there.” He was never bitten, but the sight of thousands of spiders “seething” over a fencepost is one he’ll never forget. “I’ve photographed all kinds of things in astronomy and nature, but this was in a class of its own.”

Could it happen again next year?

Thair doesn’t know how the spiders were able to survive so close together for so long. It takes a lot of energy and protein to spin a web, so the spiders must have had a ready food source while they were trapped in the field. Thair doesn’t know what it was nor does he know if they laid eggs which will survive over the winter. But he intends to examine the field more closely in coming weeks and months to find out. Thair has no patience with anyone who might be grossed out by the idea of so many spiders. “People are taught to be afraid of spiders,” he says. “That’s disgusting. Anyone who was afraid of spiders wouldn’t have gone near this, and they would have missed something extraordinary. Adults inadvertently destroy their children’s interest in science and nature by telling them to be afraid of spiders. They should stop.